Aug 15, 2013 Find out for yourself in Gone Home, a first-person game entirely about exploration, mystery and discovery. The house is yours to explore as you see fit. Open any drawer or door to investigate what's inside. Piece together the mysteries from notes and clues woven into the house itself. Discover the story of a year in the life of the Greenbriar. Unravel the mystery for yourself in Gone Home, a story exploration game from The Fullbright Company. Platforms: Mobile, Nintendo Switch, PC, PlayStation 3, PlayStation 4, Xbox 360, Xbox One. Gone Home should be considered a short game. But your playtime is really player-driven. A thorough first playthrough where you look for all the details you can find takes around 3 hours. If you rush through you can finish a first playthrough in as little as an hour. Gone Home is all about the player determining their own pace, deciding what to.

When I'm alone in someone else's home, I really can't help myself: I peek in the fridge, take a look in the medicine cabinet, and if I'm feeling particularly brave maybe I'll even root around in a drawer or two. Gone Home is a game that takes these voyeuristic tendencies and turns them into a game mechanic. The entirety of Gone Home involves searching a sprawling, empty home in order to find out what happened to its residents. You'll analyze journals and scan receipts, slowly piecing together events over the course of a few hours. On paper, it's just about the dullest-sounding game imaginable. But in practice it's a stunningly emotional story told almost exclusively through the environment.

Gone Home puts you in the role of a young American college student who has just returned from a year-long European adventure. Your family moved into a big new home while you were gone, but when you arrive at the front door both your parents and sister are missing. There's a note taped to the entrance from Sam, your younger sister, urging you not to go looking for her. Naturally, all this does is make you even more curious.

That's all of the setup Gone Home provides. The entire experience hinges on whether or not you find it compelling enough to investigate further. Gone Home's story reveals itself slowly, and much of it is inferred. You learn that your dad is a struggling author when you spot a box of unsold books in a closet and an empty liquor bottle hiding on a top shelf. Your sister's difficulty at her new school comes to light through letters from the principal and notes passed back and forth with a classmate. Every so often you'll be able to listen to Sam read excerpts from her diary, further fueling your interest in learning just what happened while you were away.

'Your mind fills in the gaps better than we could.'

At no point do you actually see these people, yet over the course of the game you really feel like you know them. And not just as one-dimensional characters — the struggling author, the troubled high school student — but as real people. 'At one point we discussed, and even prototyped, having another character show up as a surprise,' says Steve Gaynor, from developer The Fullbright Company. 'But in the end it just wasn't right for the game. In a video game, I think that on some level it's much easier to connect with a character that you never see face to face; the voice and their presence in the world is that much stronger for you never actually having to be in the same room with them. Your mind fills in the gaps better than we could.'

Gaynor previously served as the lead designer on 'Minerva's Den,' an add-on story campaign for Bioshock 2 that shares a few similarities with Gone Home. You play as a silent character from a first-person perspective, and your interaction with other people largely comes from audio clues. They may be drastically different thematically, but Gone Home almost feels like a Bioshock game with all of the violence and traditional video game challenges stripped away. It's like if you were able to explore Bioshock Infinite's floating city Columbia without having to worry about shooting dudes in the head.

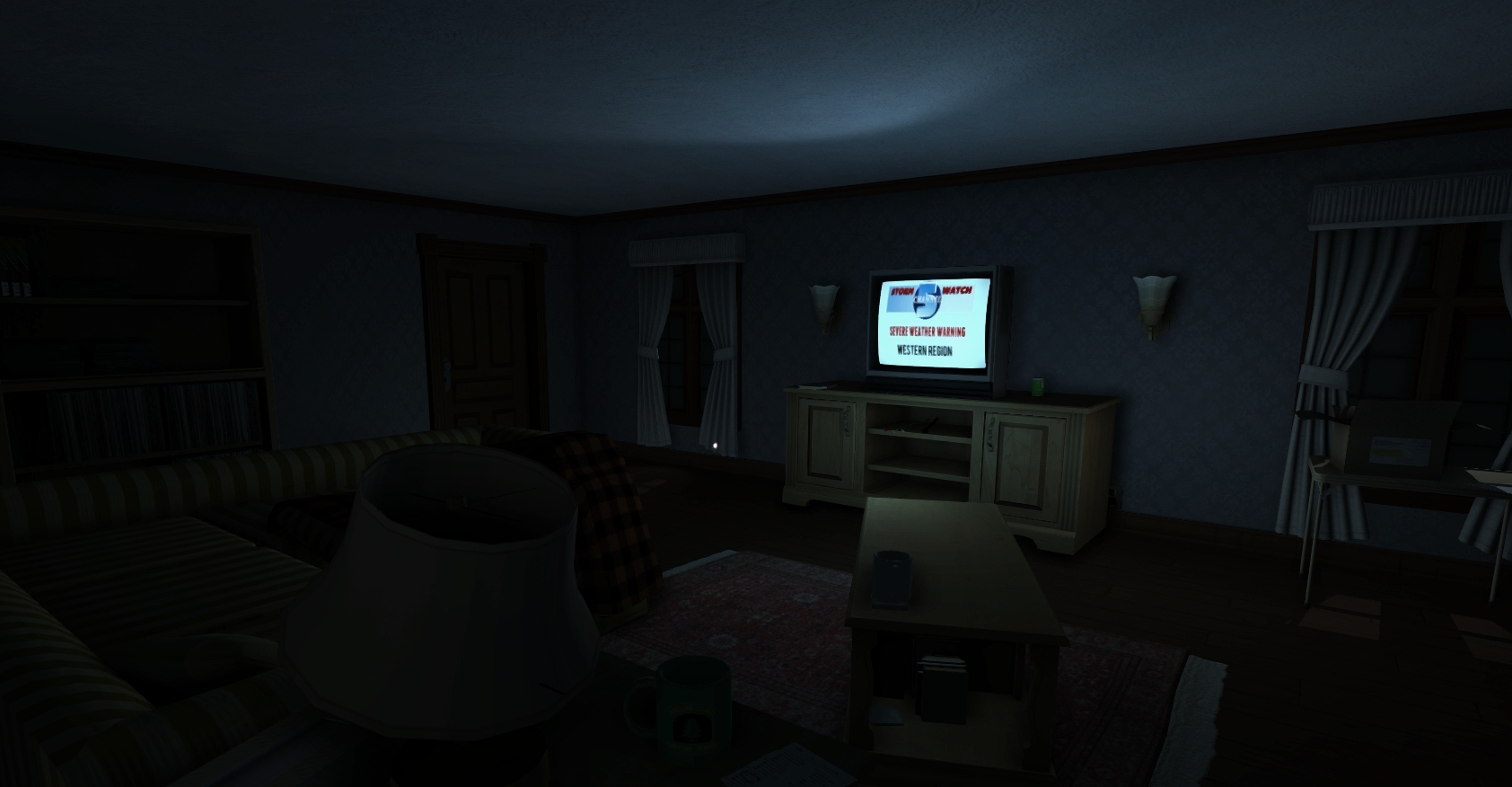

Gone Home is also something of a period piece. It's set in 1995, and the plentiful references to that time will definitely spark the flames of nostalgia for players of a certain age. You'll come across a TV Guide with an episode of The X-Files circled in pencil, and you can pick up cassettes loaded with Riot Grrrl music, pop them into a tape recorder, and rock out. All of these small details help make the house in the game feel like a home; a real place where real people live. The letters and scraps of paper scattered about don't feel like they were left there for you to find; they just feel like they should be there.

All of these small details help make the house in the game feel like a home

'I think most of it is implying a believable space — that yes, the foyer connects to the east hall connects to the family room connects to a closet,' says Gaynor. 'And that any individual room you're in is believable when you stand in it. But if you were to compare the house in Gone Home to a real, lived-in space, you'd find much much less clutter in the game vs. reality. But as long as it reads as believable in the moment, no one is actually doing that side-by-side comparison while they play, and they stay in a mindset of the place being real.'

The game is the first release from the small, Portland-based studio, and it's something of a risk: it features no weapons or violence, little in the way of traditional gameplay, an almost entirely female cast of characters, and story elements that fall outside the norm of most mainstream video games. (I won't spoil them here, but you should definitely play the game through to the end.) And that's exactly what the team was aiming to do. 'We hope that some people who are tired of those things, or who never connected with games in the first place, might get into Gone Home specifically because it's different,' says Gaynor.

Gone Home is available on Steam now for Windows, Mac, and Linux.

When playing video games, it is usually evident that the character you are playing has certain traits that set them apart from other figures within the game. These characteristics ultimately build the story of your identity in the game and give you an idea of the games objective; if there is one. It is sometimes the case that the game provides you with a bit of details before it commences; on what the storyline within the game is. In Gone Home the game opens with a phone call home, from who seems to be the main character. As the game proceeds, we learn more about the other characters within the game than we do about our actual character, who seems to be somewhat neutral in the sense that anyone playing the game can take on the identity without any real gender restrictions. This is an interesting game angle, especially when taking “A Game of One’s Own: Towards a New Gendered Poetics of Digital Space.” by Tracy Fullerton, Jacquelyn Morie, and Celia Pearce into perspective. In this article the speakers state that the objectives of game developers should be to create an “‘androgynous space’ that engages all aspects of all persons: a space into which women and girls are invited and welcomed, but in which men and boys can also enjoy more diverse and nuanced forms of play than are typically available to them.” (Fullerton, Morie, Pearce, 2007) Using screenshot images of various scenes within Gone Home we will examine how using androgynous space allows the player to feel truly connected to the games environment. As well as developing the characters identity by learning about the other characters within the game.

As the player takes on their Gone Home exploration, they are thrust into the role of Kaitlyn Greenbriar; the older sister of Samantha and globetrotting daughter to Jane and Terrence Greenbriar. As the player tries to get sense of every character and in the household drama that took place while Katie was gone abroad, it becomes clear that Katie is first and foremost a framing device, she exists in this world so that the story can be told. However, it is also apparent that The Fullbright Company went to great lengths to actually flesh out the character of Katie and the space she’s afforded in the Greenbriar household.

The story opens with a voice message that Katie left for her family, unbeknownst to her, her family was already gone by this point. She tells them of her return and throughout the game we learn, all thanks to good old postcards, of all the places she saw in the last year. As the player explores the house, the story narrated by Sam becomes more and more personal, this builds a strange feeling. We are at once a sister and a voyeur on her story. By the end we realize the whole narration is part of a book that Sam left in the attic. The fact that she leaves the book well-lit and well placed on a climactic part the mansion combined with all the clues and hints left here and there shows that either Sam knew Katie would feel compelled to “elucidate” the mystery or it simply tells us that this is a story and they are conscious of that fact. This division between the realism of the house (everything feels like a house that has been, at least momentarily, lived in.) and this nagging feeling of narrative convenience combined with the voyeurism feelings the player is meant to feel helps build Katie as both part of the world but makes her stand out. The protagonist of the game is Katie but the protagonist of the story is Samantha.

To help make Katie part of the household, we can find hints and pieces of her life here and there throughout the house. We can find and old sex ed homework in the basement. Funnily enough its content, when juxtaposed with Samantha’s similar homework, creates an interesting imbalance between the sisters. They are incredibly different but still close enough that Sam feels compelled to tell her her story. The homework impeccability and her various award strewn around (two trophies for track events and one ambiguous “first place” ribbon) establishes Katie as the perennial “good, older sister”. It is interesting, however, that the dynamic between Sam and Katie stays warm since in traditional american households the younger, more rebellious siblings have a tendency to resent the older one as being seemingly “perfect”. It is also clear that the relationship between Katie and her parents is much less volatile than it is between Sam and the Greenbriar parents. There is no hint of any kind of resentment in the letters between Katie and her parents and no mention of her is left in the house (one exception being the note telling Sam to stop leaving lights open, as her older sister is wont to do. however, this message could easily be simply a joke directed at the player since a player wouldn’t go to the trouble of closing lights in a videogame.) Conversely, the fact that Katie is mostly absent from her parents discourse could mean negligence rather than warmth. Supporting this claim would be Katie’s room which is full of her unpacked boxes. All hints tell us that the Greenbriars have been living in this house for a good 8 to 10 months, yet no-one went to the trouble of at least unpacking her most basic stuff.

Indeed, along the game, by using spatial storytelling, what Jenkins called the “Embedded narratives” (and what corresponds to the narratives elements on which the player doesn’t have any impact on) unfold in front of us. This game is particularly effective on telling this tale thanks to the immersion it creates what is reinforced by the “sense of place” put forward in “The poetry of created space from Lana Polansky. From the beginning, the player is hooked by the announce of a mystery surrounding the disappearance of sam what immediately raise a lot of questions and with them a desire for answers (that would wake up the dormant detective in anyone).

After entering the house, the first part of what we understand to be Sam’s Journal start to play and give us just enough details for us to plunge into the space of this huge mansion and try to elucidate its mystery.

The elements of Sam history is given after finding a welcoming note for new student in a backpack in a closet and learn that Sam had a rough start in a new High school due to the house history and that she is known as “The Psycho House Girl”. Chronologically speaking it might seem weird to find this note from almost a year ago but this allows to follow a chronological story line which is translated into space thanks to clues giving hints on the story or triggering journal voice over that gives whole chunk of the main story line. With a second thought, certain objects seems out of place but the fact that this objects scattered across the game space distribute precious information that fall in place eliminating those unsettlements and push the player forward the next clue.

The next piece of journals let us know that Samantha has spotted a senior girl who plays Street Fighter with her friends, “dress somewhat punk” and who “sometimes wear an army uniform”. After finding a students note on which Sam offers to visit the house to a certain Lonnie who answers that she’s interested and will “kick her butt” at street fighter once again the player is intrigued.

It triggers a journals part and we discover that Sam has played street fighter against the punk girl and her friend and despite her training got beaten. However, she got the chance to talk with the girl and the player learn that she is Lonnie and was curious to see the psycho house. The player then understand that the story will revolve around Samantha and Lonnie relationship.

However false lead like the discovery of secret doorway or the red spot of dye along with the scary atmosphere of the game make us do wrong assumptions on what might follow. Indeed, the red spot in the bathtub (that looks like blood) happens to be dye and is the trigger toward a moment of intimacy between the two girls during which Lonnie says Sam that she found her beautiful.

We then slowly witness the relationship that bloomed between Samantha and Lonnie, their first kiss and how they start “secret dating”. At some point, Sam tell her parents about her relationship with Lonnie. She expects them to react with anger or sadness, but instead they deny it what she perceived as being denied her true self.

The relationship with Lonnie continue until summer where Lonnie is supposed to join an army basic training camp. The two girls then decide to spend their last night together and Samantha end up crying herself to sleep in Lonnie’s arms as she does not want her life to continue without Lonnie. She wakes up alone the next morning and explains in her journal how heartbroken she is and that she might just wait in the attic. Imagining the worst, the player then rush to the attic to discover the journal that have been read during the game and learn that Lonnie could not go through and join the army and asked Sam to come find her, to what Sam says yes. In the final entry, Sam apologize and promise that they will see each other again.

Terrence Greenbriar, Sam and Kaitlyn’s father, is a writer. Early in the story, we learn that he is a writer who has an interest in science fiction. Through the large number of copies of his first two books, and letters from his publisher at the time, we learn that he was not initially very successful. His first book did not do well, but in hopes that the second would sell better, Terry’s publisher still wanted to print the sequel. After a second failure, the publisher would not continue to work with him.

As Kaitlyn continues to explore the house, we learn that Terry then began working as an electronics critic. An old friend from college remembered that he was a writer, so asked if he would be interested in taking on some of the extra work that they had. Luckily, this friend managed to contact Terry shortly after his publisher had dropped him. Terry seems to continue with this employer until closer to when the story takes place where we learn that the editor of his work is not very happy with him. He had a tendency of relating his past to the object that he was to write about, which is not what the company had wanted. Through manuscripts and other notes found throughout the house, we can see how this was a big blow to Terry’s morale.

In the basement, we begin to see a glimpse of Terry’s childhood. We learn that he does not have a good relationship with his father, and that his father was not supportive of him as a writer. At this point, it does not seem like things are going too well for Terry.

After further exploration, we begin to see where things start getting better for him. We learn that another publisher found his book through a book sale, and was very interested in reprinting his work. Terry then begin to write again, and even though this particular publisher does not normally publish new work, they seem to be interested in what he is doing. There are letters found throughout the house that indicate that the relationship between Sam and her father were tense, and that he was concerned with her school. He wanted to see her succeed, so through a series of notes, he tries to talk to her about how she needs to try to fix the situation.

Gone home centres around the structure to explore, to map and to master the contested space. The physical space of the house does most of the work of conveying the storylines. The narration process is scattered information across the game space. As a player you explore the house, unlocking the secrets and discovering the pre-structured story. If we take a look at the mother’s storyline, we begin to pick up clues indicating that she was having an affair. Her secrets are quietly lying around the house, waiting to be pieced together. Although the affair is not confirmed, there are positive signs. Her husbands depression (bottle of whiskey in his study, his book not selling, the wet bar) could have driven her away. A clue that leads us to believe in the downfall of their marriage is the couples retreat pamphlet found in the house as well as the book titled “After the honeymoon: Rediscovering your spouse personally, spiritually, sexually”.

There are a few hints that indicate an affair for example: the hunky woodsman novel, the secretive notes to her friend addressing her interest and attraction in a co-worker, Ricks perfect assessment sheet, the hidden book with the bookmark with the cute little note inside hidden under her bed and lastly the concert ticket hidden under the floor vent. All these secrets demonstrate the tension and downfall in her marriage.

Despite the clues of a possible affair, nothing is certain. We find out that Rick has gotten married prior to the mother and her husband leaving on a retreat and to Katie’s return back home. Rick and the mother’s relationship could have declined as it got closer to his wedding day or it could have never existed at all and we just over read the “signs”. The fact that the mother left with her husband on the retreat is an indication that she was willing to improve her marriage.

After examining each character individually it becomes clear that although the game feels like the central character has little to no identity, she is in fact given characteristic traits as we get to know her family. The space of her house and the relationships within the household give us enough information to get a clear image of who the character is, without taking away from the element that allows anyone who is playing to feel, at home.

Work Cited

Dicket, Michele D. (2005). Engaging by Design: How Engagement Strategies in Popular

Computer and Video Games Can Inform Instructional Design. Education Technology Research

Gone Home Game Switch

and Development. Vol. 53, No. 2. pp. 67-83.

Fullerton, Tracy, Morie, Jacquelyn and Pearce, Celia. “A Game of One’s Own: Towards a New

Gendered Poetics of

Digital Space.” Proceedings of perthDAC 2007: The 7th International Digital Arts and

Gone Home Game Safe

Culture

Conference: The Future of Digital Media Culture. 2007.

a-new-gendered-poetics-of-digital-space/

Gone Home Game Wiki

Polansky, Lana. “The Poetry of Created Space.” Bit Creature. 5 October 2012.

Jenkins, Henry. “GAME DESIGN AS NARRATIVE ARCHITECTURE”. 2003